Keeper Of The Flame Vol.1

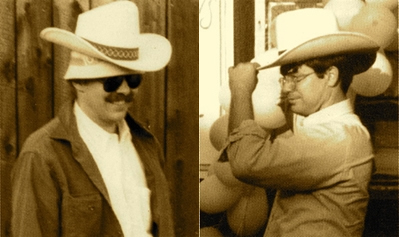

みずがめ座の時代が終わろうとしていた1970年、コロラド州クレステッドビュートの、とあるバーレストラン。デファイアントの伝説はその店に通う二人の青年によって、どこにでもある日常の中から始まった。 Tailingsの共同経営者であったマーリー・ハウエルは当時25歳、ペンシルバニア大学の政治学を卒業した彼はバーの裏手に勤務していた。32歳のダンカン・サイム、イエール大で学んだ造形家であり建築家の彼はあてもなくその町にいた。

二人は毎晩店を訪れてはバドワイザーをすすり、ジュークボックスを聞きながら思いをめぐらしていた。青年なら誰もが考えるであろうこと、この先何をしたらいいのだろうかと。二人はいろいろ話しただろう、田舎に帰りニューイングランドのどこか静かな町に住むのがいいんじゃないか?誇れる何かを築き上げ、サラリーマンの過酷さから自由になり、実直な職人として働き仲間として暮らしていくのはどうか?

彼らはその空想を‘ニューハンプシャー ボールベアリング工場’と名付け、いつか一緒に始めようと約束したビジネス構想の速記を共有した。何を作れるのかはっきりとはわからなかった。しかし全ての人の心を掴む魔法である‘稀有で独特な’何かでなければならないと二人は考えていた。

二人は東部へ戻り、時は流れ1975年。スーツとネクタイに身を包んだハウエルはニューヨーク市ラザルドフレル社で働いていた。一方ハウエルの姉と結婚したサイムは、バーモント州の小さな町ウォーレンですき間風の入る木材屋に住み、エネルギー効率のよい家を建てようと奮闘していたが、運に恵まれず暗中模索の状態であった。

カウンターカルチャーのニューイングランドでは、薪ストーブは冬の時期どこにでもあるものらしかった。サイムもモントゴメリーウォード社製の古い石炭バーナーを改造して暖をとっていた。そして特に霜の降りるほど寒かった3月のある晩、火に薪をくべていなかったサイムは夜着で氷点下11度(-11度C)の肌寒い外へ向かった。

サイムはいろいろな修繕をしていた。彼は最初のうちはストーブのビジネスを始めようとは考えておらず、ただ自分で使うためのより良いストーブを作りたいだけだった。「それで、その辺にあるストーブを見てみたけど、ちゃんと機能しないものがほとんどなんだ。中には十分な機能を持つものもあるけど、デザインが最悪で…。」彼はニューヨークでハウエルにそう話した ―― これはチャンスじゃないのか?ハウエルは市場の好機をうかがってきた。 OPECの誕生に伴い、石油価格は上昇、薪による暖は人気があった。経済的・環境に良さそうなだけでなく、道徳上正しいことのようにも思えた。エクソン、シェル、そして石油王族からの自立を示すひとつの方法だった。そのきっかけから2年間で、輸入物のヨツールは4万台ほどの数を売り上げたと言われた。 19世紀のデザインで薪の消費が激しくその機能性の悪さと同じくらい見た目もひどい巨大なストーブを販売していたアメリカのストーブ会社でさえ拡大していった。そこでハウエルは新事業の元手25,000ドルと共に、バーモントへ移った。

彼らの目標は控えめなものだった。サイムは言う、「私達は市場に出ている他のストーブよりも見た目が良くて、できればちょっと機能性も高いものを作れたらそれで良かった。」 競争力のあるストーブがすでに市場に存在するなかハウエルは ‘ストーブレース’をひた走った。サイムはデザインを描くかたわら、薪燃焼についての授業を受けた。そして彼はとうとう躍進の突破口となるものを発見したのだ。リタイアした教授の地下室に眠っていた薪の蒸留分離についての第二次世界大戦学術研究の資料である。これはバーモントキャスティングス製品にとって類のないサイドドラフト(水平)燃焼システムという画期的な性質の基礎となった。そして彼の芸術的外観への注目は結果として、ニューイングランドの建築デザインのモチーフを使うという特徴を定義づけた。

サイムはストーブの型を作るため、ウォーレンバーモントのボビンミルという使われていない工場に木材作業場のスペースを借りた。ハーバードで建築を学んだバンス・スミスは、ストーブ設計に意見を出し、プロジェクトを進めていくサイムに協力した。彼らはバーモント州ランドルフにあるもっと大きい工場に移り、会社をバーモントキャスティングスと名付けた。バンス・スミスはデザイン、広告、マーケティングにおいてハウエルとサイムと共に仕事をした。

冬の風をものともしない(defy) という能力から、最初のストーブをデファイントと名付けた。実際それは他のものより少し良いものどころか、かなり優れたものだった。他のストーブは薪による熱温度の40%しか最高でも放出できないのに対し、デファイアントは気密とサーモスタットでコントロールされているため60%の放出が可能だった。他のストーブは不格好な箱のようであったが、サイムのデザインしたデファイアントはまるで家宝の家具のように見えた。家を暖めるだけの他のストーブと違い、デファイアントは心まで温かくしてくれた。ドアを大きく開けてサイムがしたように、覆いのない炎の前でうたた寝したくなるようなものだった。

‘気のきいた金属製品’サイムは控えめにそう呼んだ。‘もし運が良ければ、一年で10,000ドルを私とハウエルで稼げるくらいには売れるのではないかと思った。それだけあれば美しい町に住んで、したいことをして生活するのに十分だ。’ しかし実際、最初の200台はデザイン画の段階で売れた。まだ製造を開始する前であったにもかかわらず。1年で売上高はおよそ25万ドルにもなった。 5年で彼らはアメリカで最も早く急成長を遂げたストーブ会社となった。

デファイアントはひとつの現象だった。アップルコンピューターのように、製品と同じように象徴化して例えられることとなった。ショールームに集まる客はただストーブを買うだけでなく、バーモントキャスティングスの会員となり‘オーナーズニュース’を読み、無料ダイヤルでバーモント州ランドルフのストーブ愛好家同士で連絡を取り合い、燃焼時間や薪の量について話したのである。そこまで客の思い入れが強い製品はかつてほとんどなかった。得意客はバーモント社の職人にお礼の手紙や、ストーブを囲んでとった家族写真付きのクリスマスカードを送ったりした。

ストーブを組み立てるのには時間がかかった、生産に間に合わないほどしかしサイムは言った。「販売活動は大事だ、でもそれがどうだっていうんだ。」 製品コストと経費に50%のマージン、更に販売店に30%のマージンをつけている為、製品は高く値段設定されていた。しかし値段は問題ではなかったようだ。固定客はついて、商品を買いに訪れ、口コミや刊行物の熱のこもった話などに惹きつけられていた。販売業者にマージンを払う必要があるのだろうか?特定の地域で配布されるチラシを通信販売制にして、顧客基盤を上ミシガン半島からカリフォルニア州のビッグサー地方まで拡大させた。デファイアントを無理に宣伝する必要はなく、その質の高さと芸術的追求だけで十分だった。要求に見合うまで6年ほどかかったが、注文と現金は絶え間なく続いた。

翻訳:沐日社

Keeper Of The Flame

The legend of the Defiant began prosaically enough with two young men in a bar and grill in Crested Butte, Colorado, in 1970 — the tail end of the Age of Aquarius. Twenty-five-year-old Murray Howell, co-owner of The Tailings, was a University of Pennsylvania political-science graduate getting his head together, working behind the bar. Thirty-two-year-old Duncan Syme, a Yale-trained sculptor and architect, was drifting through town.

Night after night the two would sit, sipping their Budweisers and listening to the jukebox, wondering, as young men will, what to do with their lives. Wouldn’t it be nice to move back to the land, they’d ask each other, to live in rural New England? To work as honest craftsmen and live as brothers, building something to be proud of, free from the tyranny of suit and tie?

They even developed a name for the vision: “the New Hampshire ball-bearing factory,” they called it, shared shorthand for the business they promised they would start together. They didn’t know what they could build, exactly. But they agreed it would have to be something “rare and unusual,” magic for everyone it touched.

Flash forward to 1975, after the two friends have moved back East. Howell, in suit and tie, was working for New York City’s Lazard Frères & Co. Syme, now married to Howell’s sister, was still drifting, a subsistence architect trying, without much luck, to build energy-efficient houses in tiny Warren, Vt., living in a drafty wood shop.

Wood stoves seemed to be everywhere that winter in counterculture New England. Syme himself heated with an old Montgomery Ward coal burner he’d converted. Then one particularly frosty March night Syme didn’t get up to feed the fire, and he woke up to an 11-degree chill outside his covers.

Syme was a tinkerer. He wasn’t thinking about starting a stove business initially; all he wanted was to build himself a better stove. “But then I looked at the stoves that were around. Most of them didn’t work very well. A few worked well enough but looked terrible.” So he talked with Howell in New York — could this be their chance?

Howell had seen the market opportunity himself. With the birth of OPEC and the rise of oil prices, wood heating was hot — not only economically and environmentally sound, but morally righteous, a way to assert your independence from Exxon, Shell, and the oil sheiks. In the two years since its introduction, sales of the imported Jotul were said to be as high as 40,000 units. Even U.S. stove companies were growing, selling giant wood-eating behemoths designed in the nineteenth century, as ugly as they were inefficient. So Howell moved up to Vermont with $25,000 in seed money.

Their intentions were modest, Syme says. “We wanted to make a stove that was better looking than anything else on the market — and worked a little better, too, if possible.” Howell ran “stove races,” competitive firings of the stoves already on the market. Syme sketched out designs and gave himself a crash course in wood burning. He stumbled eventually onto the breakthrough resource: boxes of World War II research on the distillation of wood, moldering in the cellar of a retired professor. This was the basis of the revolutionary side draft combustion system that is unique tot he Vermont Castings products. His attention to aesthetics resulted in the defining characteristic of using New England architecture design motifs.

Syme rented wood workshop space in an abandoned factory called the Bobbin Mill in Warren Vermont to build the patterns for the stove. Vance Smith, a Harvard-educated architect noticed Syme designing the stove and joined him on the project. They moved into a larger abandoned factory on Prince Street in Randolph, Vermont and named the company Vermont Castings. Vance Smith worked with Howell and Syme on design, advertising and marketing.

They called their first stove the Defiant, for its ability to defy the winter winds. And it wasn’t a little better, it was a lot better. Other stoves delivered, at most, 40% of the wood’s heat. The Defiant, airtight and thermostatically controlled, delivered 60%. Other stoves were ungainly boxes; Syme’s Defiant looked like heirloom furniture. Other stoves could warm your house. The Defiant could warm your heart, with doors you could swing wide if, like Syme, you wanted to sit and dream in front of an open flame.

“A sensible piece of hardware,” Syme called it modestly. “I thought if we were lucky we could sell enough that Murray and I could make $10,000 a year, enough to live in a beautiful area and do what we wanted.” Instead, they sold their first 200 units before they started production, on the basis of their design sketches alone.

Within a year they had sold some $250,000 worth.

Within five years they were on the Inc. 500, the fastest-growing stove company in America.

The Defiant was a phenomenon. Like the Apple computer, to which it was widely compared, it was as much a symbol as a product. The customers who flocked to the showroom weren’t just buying a stove, they were buying membership in a tribe, bound into the Vermont Castings dream through the “Owners’ News” and a toll-free line that would put you in touch with a fellow stove freak back in Randolph, Vt., ready to talk burn times and cords. Few products have ever won as much customer loyalty: proud owners sent thank-you notes to the Vermont craftsmen who built it, or Christmas cards with their stoves the center of the family picture.

“Marketing, schmarketing,” Syme said; they couldn’t build stoves fast enough. They priced their product high, adding a 50% margin to their costs and operating expenses, then adding another 30% margin for their dealers. But the price didn’t seem to matter. From day one a steady stream of customers had shown up at their door, cash in hand, drawn by word of mouth or one of the growing number of glowing stories in the press. Why pay a dealer’s margin? One flier, circulated locally, led them into mail order, and a customer base that stretched through Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and into California’s Big Sur. There was no need to pitch the Defiant; its quality and artistry spoke for themselves. It would take six years to catch up with demand: the orders and the cash just kept flowing in.